Magazine

The Union that Should be

From Bentley Director Terrence J. McDonald

This has been a busy summer for historians. Outbreaks of neo-Nazi and white supremacist ideologies and organizations — most prominently seen in Charlottesville, Virginia — have put the question of how we appropriately remember and commemorate the American past squarely on the table.

The neo-Nazis and white supremacists were marching together in Charlottesville to “protect” the monuments to the Confederacy there. There are no monuments to the Confederacy in Michigan. It’s worth remembering why not.

The birth certificate of the state of Michigan, the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, banned slavery in the “old” Northwest, the territory that would become the states of Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Wisconsin. The founding fathers who voted on this Ordinance—Thomas Jefferson wrote the first draft—failed to eliminate slavery from where it existed, but they voted to prevent it where they could because they knew it was antithetical to the egalitarian society they hoped to build further west. It was this ordinance that called for free public education at all levels and, therefore, led to the founding of the University of Michigan, too.

While the states of the old Northwest were not racial paradises by any means, they were born free from slavery. They contributed around one million members of the Union army, who fought to put down the Confederacy, which they correctly believed was the “slave power.” Ninety thousand of these troops were from Michigan; 85,000 of the Michigan troops were volunteers.

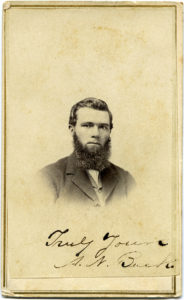

Andrew Newton Buck. HS17465

Because we have the Buck family archives at the Bentley, we know two of them. Andrew Newton Buck fought his way through the Civil War as a member of the Union cavalry. He served under Custer at the Battle of Gettysburg, where his horse was shot out from under him. His brother Curtis served in the Union artillery. They were raised in Englishville, in Kent County, and both survived the war. Curtis would graduate from the U-M Law School in 1872.

In 1864, 25-year-old Andrew Newton Buck wrote home from the battlefield near Stevensburg, Virginia, assuring his father and sister that “the rebellion is dying for the very simple reason that it cannot live.” With the death of slavery, he wrote, “we shall have the ‘should be’ not the ‘was’ Union.”

What a wonderful sentiment on which to reflect today, when there are those who seem to want to take us back to the “was” Union. The “should be” Union requires that we forget nothing about our past. But it also requires due deliberation about what we as a society commemorate.

At the Bentley, our judgment about which archives to collect is based strictly on historical value. In order that we remember everything, our archives hold the remaining hard copies of the Michigan Ku Klux Klan newspaper from the 1920s and every issue of the decidedly left-of-center Detroit newspaper, the Michigan Citizen.

We are proud to hold the papers of Frank Murphy, Detroit judge and Mayor, Governor of Michigan and the Philippines, and author of the heroic Supreme Court dissent in the Korematsu v. United States case in which he denounced the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II (see our story on page eight). But we also have the archives of Gerald L. K. Smith, notorious anti-Semite and “America First” party founder.

The Union that “should be” and Union that “was.”

Our archives help us all tell the difference.