Magazine

The Unsinkable Sarah E. Ray

In 1945, Sarah Elizabeth Ray was denied passage on a ferry on the Detroit River because she was Black. She fought the injustice, and her case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. For decades, Sarah’s trailblazing civil rights role was nearly forgotten, as was her work later in life as a community activist. But thanks to the work of historians, researchers, archivists, and members of her family, her legacy is being preserved—including through a new collection coming to the Bentley Historical Library.

By Lara Zielin

On a bright summer day in 1945, Sarah E. Ray was ready to celebrate.

As part of her work at the Detroit Ordnance District, she and a handful of other women had successfully completed extra training, and this was their graduation day.

To mark the occasion, the group decided to board a Bob-Lo boat, one of two large passenger steamboats that regularly ferried customers down the Detroit River to Bob-Lo Island. There, passengers could enjoy an amusement park with rides, food, and games.

Sarah got her ticket and boarded the Bob-Lo boat with her group, but she didn’t make it very far.

She was told that she wasn’t allowed on the boat due to the color of her skin. Sarah refused to disembark until her teacher said, “She’ll go quietly.” Sarah was escorted off the ship, angry and humiliated.

When the Bob-Lo ticketing booth gave her a refund, she hurled the money directly at the ship. She would not be bought.

Sarah’s story could have ended there, but she was determined to seek justice for the discrimination she’d endured. What happened next helped change the course of civil rights history— as important a legacy as Rosa Parks refusing to take a different seat on the bus or Ruby Bridges walking into an all-white school in New Orleans.

Except Sarah’s story never made it to the history books. Or at least not until recently.

Now, thanks to the work of historians, researchers, and her family, Sarah’s incredible story is becoming better known. Bentley archivists have been working on Sarah’s story as well, ensuring that her materials will be safeguarded in the archive and that her transformational legacy is widely shared.

The Bob-Lo Excursion Company would try to sink Sarah, but she would be the one who would triumph on the Detroit River— and beyond.

All the Way to the Supreme Court

After being forced off the Bob-Lo boat, Sarah got to work contacting the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) for help with her case. According to the Michigan Civil Rights Act, it was illegal to discriminate in public conveyances—such as buses or boats—on the basis of race. Sarah knew that what had happened to her was illegal; she just needed help proving it.

The NAACP took Sarah’s case to court. At every level, the courts ruled in her favor, but the Bob-Lo Boat Excursion Company appealed, arguing that because the boats were going to Canada, the Michigan Civil Rights Act didn’t apply to them.

Eventually, the case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. The NAACP Legal Defense Fund chief counsel working on behalf of Sarah was a young, energetic lawyer named Thurgood Marshall. The grandson of an enslaved person, Marshall was building a name for himself as a tireless fighter against racial discrimination.

In 1948, the Supreme Court ruled against the Bob-Lo Excursion Company. The court said the company “will be required in operating its ships as ‘public conveyances’ to accept as passengers persons of the Negro race.”

Five years later, Marshall would be back in front of the Supreme Court arguing the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka case, which ended the “separate but equal” policy in schools. Scholars argue that Sarah’s case paved the way for these larger, national victories.

“Her win was an indication that the U.S. Supreme Court had an appetite for cases like Sarah’s,” says author, Pulitzer Prize-nominated journalist, and former attorney Desiree Cooper. “The NAACP had a strategy that was long and slow, but it worked. Thurgood Marshall could bring a big case like Brown v. Board to the Court after smaller cases like Sarah’s had paved the way.”

Cooper acknowledges that often, in this process, the early pioneers like Sarah pay a high price. “We tend to think that change happens seismically, and what we don’t quite get is that it’s a chipping, chipping until change happens. And the people who chip, quite often when they start, are very alone and do it at great personal risk.”

Cooper was a reporter for the Detroit Free Press when she met Sarah in February 2006. She got a tip about the story and went to Sarah’s east-side Detroit home to interview her.

“The house was falling down, and there were abandoned houses on the street,” says Cooper. “Inside was orderly but very cold, and Sarah was bundled up. Because of her arthritis, she had a hard time getting around. She said, ‘I would offer you tea, but it’s too hard for me to get into the kitchen.’”

Cooper says that it was difficult seeing Sarah in this state. “It was very clear to me she was a forgotten person,” Cooper says. “But she was very present in her mind. She told me the story [of being on the boat in 1945] the same way she told it in her testimony early on, and the thing I walked away with is that she was still really pissed off about what happened.”

Cooper wrote an article for the Detroit Free Press about Sarah’s story and her contributions to the Civil Rights Movement. Not long after its publication in 2006, Sarah died at age 88. Her house fell into disrepair and her legacy seemed like it would be lost forever.

That is, until a filmmaker started working on a documentary that would change everything.

An Old-Fashioned Trailblazer

In 2015, Aaron Schillinger was in the process of creating a documentary about the two Bob-Lo steamships—the Columbia and the St. Claire—called Bob-Lo Boats: A Detroit Ferry Tale. A New York University film graduate, Schillinger was doing research when he stumbled on the book Summer Dreams by Patrick Livingston, which briefly mentioned Sarah’s story. When he went to dig further into the story, he hit numerous dead ends.

“I couldn’t find any photos, and there was almost nothing online when I first started looking,” he says. He decided to include Sarah’s story in his documentary, but ultimately had to depict her using stop-motion animation because of the dearth of materials available.

Then, he located Cooper’s 2006 story in the Free Press.

He flew down to Virginia to interview Cooper for the documentary, learning more about Sarah’s role in the Detroit community in the 1960s. After the 1967 Detroit rebellion, Sarah and her second husband, a Jewish labor activist named Rafael Haskell, bought a building that could serve their local community and poor people. They called it Action House.

Through Action House, Sarah fought for social justice and created recreational activities for neighborhood youth. She was a fierce believer in integration when, post-uprising, the idea was losing popularity.

“While she was a trailblazer, she was also oddly old fashioned,” says Cooper. “At that time, integration wasn’t the watch word, it was Black nationalism, and here she is talking about integration and she is married to a white man.”

Sarah aligned herself with activists and popular social justice advocates like Harry Belafonte. She wrote letters to and networked with local Detroit leaders.

Cooper and Schillinger uncovered much about Sarah’s life before and after the Bob-Lo boat incident, yet there was still so much they didn’t know.

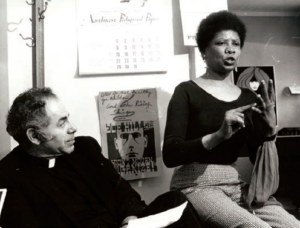

Sarah was a grassroots community organizer in Detroit, often collaborating with local leaders like Father Robert Zerafa, pictured here with Sarah in March 1971.

Part of the challenge was that Sarah E. Ray had numerous name changes over time. Born Elizabeth Cole in 1921, she married her first husband, Frank Ray, in 1936 and came to Detroit during the Great Migration as Sarah Elizabeth Ray. In the 1940s, she dropped “Sarah” and started going by her middle name, Elizabeth. When she married Rafael Haskell, she started going by Elizabeth Haskell or often Lizz Haskell.

“That made tracing her history so much harder,” says Cooper. “Her name was fumbled all the way around because, even on ancestry websites, her name is sometimes Raye. You really have to dig hard in order to link up what name she was using and what she was doing.”

As Schillinger and Cooper built their body of work around Sarah, they also discovered that her Detroit home was slated for demolition. “The Land Bank owned the property, and we were able to coordinate with the mayor’s office to get it off the demolition list,” says Schillinger. But finding someone who could save it became part of their work, too.

“I was in disbelief when I went into the house and I could just pick up a piece of paper with Lizz Haskell’s name on it,” says Schillinger. He describes photos, letters, poetry, art, and personal possessions rotting inside the abandoned structure. “That led us to think about how we could extract these materials, and how could we find a place to serve as a repository for them to be preserved.”

Together, Schillinger and Cooper created the Sarah E. Ray Project to frame Sarah’s story, share her history, find help for her house and materials, and collect more information. They were even able to get the National Trust for Historic Preservation to name Sarah’s former home one of America’s “11 Most Endangered Historic Sites” in 2021.

In the process, they also tracked down a living relative of Sarah: her great grand-nephew, Kourtney Thompson.

Taken Aback

Thompson remembers visiting his “Aunt Lizz” and having holiday meals with her when he was young. And he remembers that she was a fierce advocate for reading and education, helping inspire him to attend U-M and become the first member of his family to go to college. After graduating in 1990, he spent his career in Detroit as a social studies and physical education teacher.

Even so, he had no idea that Aunt Lizz was Sarah E. Ray and that she had been instrumental in desegregating the Bob-Lo boats. “Before she died, I had started handling some of her affairs, and we came across [Desiree Cooper’s] article. I was taken aback by it, the comparison with Rosa Parks—we just didn’t know.”

Thompson collected materials from Sarah’s Detroit home as well as what he could find in his own family materials. Through Cooper and Schillinger, Thompson was then connected to Michelle McClellan, the Johanna Meijer Magoon Principal Archivist at the Bentley Library about archiving Sarah’s papers.

Singer and social justice advocate Harry Belafonte with Sarah in an undated photo.

“I instantly understood the value of this collection and the importance of Sarah in showing the key roles that women of color have played in national civil rights history,” says McClellan. “I wanted Kourtney to know that when this collection came to the Bentley, we would be protecting it, preserving it, and making it available for people to see. Donating the material to the Bentley is an extension of the process of rediscovering Sarah’s life and contributions.”

Thompson says that he knew the Bentley was the right place for his great-aunt’s papers. “I was a U-M man, I played baseball there, and I’m proud of its reputation. If anyone is going to have possession of these artifacts from someone who made this society better, U-M is the place.”

A Complete Person

After Sarah was cremated, Thompson took her ashes to the Canadian side of Belle Isle—a small island on the Detroit River between the city of Detroit and Canada. “She wanted to be free on that river, to ride the boat, and she can do that now after her death,” says Thompson. “Wherever that river may go, she can go, she can do it as a free soul.”

Thompson says that his great-aunt’s legacy goes beyond just the Bob-Lo boats. “She was the woman who brought the lawsuit, yes, but she was more than that. She was someone who was well connected, who was well read, who served her community, who fought for human rights. She was making change in her community where it mattered most.

“That’s what I would like to have remembered—the fact that she was a complete person. She wanted what everyone wants: dignity, recognition, respect, and the opportunity to live freely. That’s what we all want in the end, to go places where we feel respected, safe, and cared for.”

[Lead Image: The Bob-Lo ferry Columbia, from a February 2006 Detroit Free Press article about Sarah Ray archived at the Bentley Historical Library.]