Magazine

Tragedy on the Ice

When a faculty member recommends his prize pupil for a daring expedition in Greenland, disaster strikes on multiple fronts.

By Andrew Rutledge

Tucked into the alumni file of Edward Israel is a hand-written copy of an article about the 1881 graduate. It describes Israel as “a man of unusual character who, had he not been cut off at the early age of 25, would undoubtedly have left a decided impress on the world.”

The article appeared in a strange place—the American Meteorological Journal—and was written by Israel’s mentor, Mark Walrod Harrington, third director of the University’s Detroit Observatory. It wasn’t exactly commonplace for faculty to write articles in academic journals about former students, let alone students who weren’t scholars in that field. So why did Harrington pick up his pen and write so eloquently about Israel?

The answer may be, in part, guilt.

The Arctic Astronomer

In early 1881, Harrington was asked to nominate a student to serve as the astronomer for an expedition to the Arctic called the Lady Franklin Bay Expedition. His mind went immediately to his prize pupil: Edward Israel.

Born to Jewish parents who had come to Kalamazoo, Michigan, from Germany, Israel had entered U-M in 1877 and excelled at astronomy. Harrington wrote later that he approached Israel “with some hesitation” about the Arctic expedition since “[Israel’s] circumstances in life were so easy, he could pursue any line of study he might select, [but] on consulting him, the only motive which restrained him was a knowledge of the pain his acceptance would cause his [widowed] mother.”

Eventually, Israel’s mother gave her blessing, and Israel accepted the nomination. The expedition’s departure date forced Israel to leave Michigan before his final exams. The Board of Regents made a special dispensation to grant him his degree in absentia, something normally forbidden by University rules.

The Lady Franklin Bay Expedition had its origins in the first ever International Polar Year, which sought for the first time to create a coordinated approach for exploring the Arctic. Led by Lieutenant Adolphus Greely, the expedition’s goal was to establish a research station at Lady Franklin Bay on Ellesmere Island west of Greenland. The team planned to spend two years there collecting tidal, meteorological, astronomical, and magnetic data, as well as exploring the region for future expeditions to the North Pole.

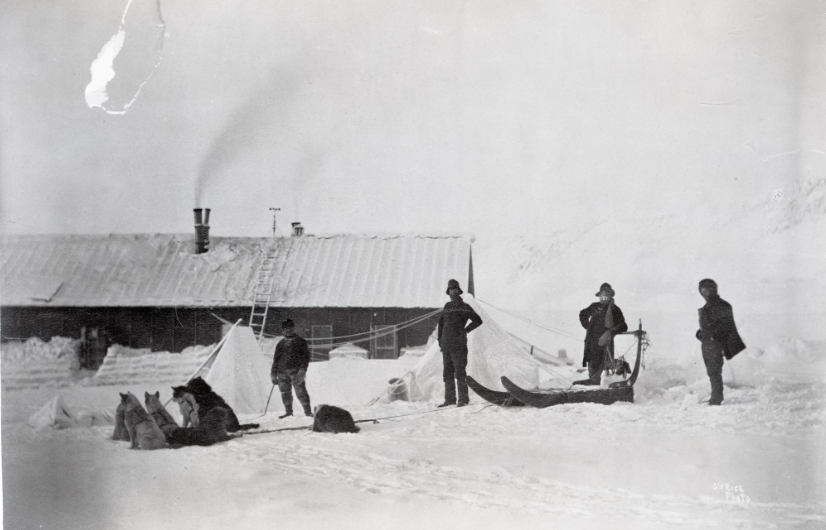

Israel, Greely, and 23 other men left for the Arctic in July 1881, stopping in Greenland only long enough to hire a pair of Inuit sled drivers and a doctor. By August, they had reached their destination and the 25 men began building the longhouse that would be their new home. They dubbed it Fort Conger, after expedition sponsor Senator Omar Conger of Michigan, and would spend the next two years there—farther north than any other humans in the world.

Fort Conger after its completion. [Library of Congress]

During the following months, Israel played a key role in collecting the expedition’s scientific data, while other members of the party traveled north, coming closer to the North Pole than any explorers had before. But despite these scientific successes, all was not well. Unbeknownst to Greely or his men, the summer of 1881 had been extraordinarily warm, allowing them to sail through open water to Fort Conger. That was not to be repeated.

By the summer of 1882, the men were expecting their first supply ship, but it was blocked by ice hundreds of miles to the south. Eventually, it was forced to turn back. A second attempt in 1883 ended with the relief vessel crushed by ice. Unaware of any of this, but knowing that his men were in danger of starving, Greely ordered his team into boats on August 9, 1882. Their goal was Cape Sabine 250 miles to the south, where the relief expeditions had been ordered to leave their supplies if they were unable to reach Greely.

After a nightmarish 51 days at sea, during which Israel’s astronomical skills proved vital for navigation, the group reached Cape Sabine. To their horror they found only a fraction of the supplies they had expected; there were only 40 days’ worth of rations, which they would have to make last until the following summer.

Warmly Loved by All the Men

On January 18, 1884, the first member of the expedition succumbed to scurvy and malnutrition. He would not be the last. Over the following months, men died one by one, trying to survive on tiny shrimp from the bay along with candlewax, boots, bird droppings, and anything else remotely edible.

One man was caught stealing food from the others and was shot on Greely’s orders. In an effort to stay warm, the survivors shared sleeping bags. Israel paired with Greely, who described him “as a great comfort and consolation to me, during the long weary winter . . . He was warmly loved by all the men.”

Edward Israel died “very easily and after losing consciousness” on May 27, 1884.

Twenty-six days later, rescue finally arrived. By then, there were only seven survivors, one of whom died soon after. Greely and the others returned to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, to a hero’s welcome. But worse was yet to come.

Soon, rumors of cannibalism arose among the rescuers who had seen the corpses at Cape Sabine. An autopsy on the body of Frederick Kislingbury, second in command of the expedition, found flesh had been cut from his bones. The survivors all stridently denied any knowledge of cannibalism, with some suggesting that those fishing may have used corpse meat for shrimp bait.

Edward Israel’s body was not among those reportedly mutilated, but his mother refused to allow an autopsy. When his remains arrived in Kalamazoo, nearly the entire city greeted it. The funeral was held that same day. His mother would later donate 50 arctic plants he had collected to the University’s collections.

As for Israel’s mentor, Mark Harrington, he too met a tragic fate. After leaving U-M to head the U.S. Weather Bureau in 1891, he briefly became the president of the University of Washington. One night in 1899, he told his wife he was going out to dinner and disappeared. For the next decade there was no sign of him, until his son found him in an asylum in New Jersey in 1908. Sadly, Harrington did not recognize either his son or even his own name. He never recovered, spending the remainder of his life in the asylum before passing away in 1926.

[Thumbnail image at the top of the story: Edward Israel, circled, with other members of the expedition before they embarked for Greenland.]