Magazine

Up, Lad, Up

John Nakamura was a smart, conscientious U-M student hoping to become a journalist. Then Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941, and the United States entered World War II. Archived papers at the Bentley tell the story of how Nakamura’s path was altered, but never his heart.

By Kim Clarke

As a journalism student at Flint Central High School, John Nakamura faced a daunting assignment: write your own obituary.

He was just a teenager, so what to say? He had loving parents, four brothers, and a sister. Together, they were the city’s first Japanese American family, living in a two-story house his immigrant father had designed.

He loved to read and dance. He played the trumpet and was known to perform “Taps” on Armistice Day.

Johnny Nakamura closed his obituary with a two-word epitaph he imagined for his headstone:

“I? Why?”

As papers at the Bentley Historical Library reveal, he would provide many answers in the years ahead.

A Spirit of Democracy

Nakamura enrolled at U-M in 1940 after earning an associate’s degree at Flint Junior College. He settled into Congress House, a student cooperative on Tappan Avenue, a few blocks south of the Law Quad. Co-op living was a draw because of the cheap rent and rich camaraderie. Students filled the house with used furniture, dented pots and pans, and battered utensils. Everyone pitched in—shopping, cleaning, cooking, partying—to keep down costs.

“Living in the co-ops I won’t be troubled by the question of expenses that can really upset a student’s life by worry and anxiety,” he told his parents.

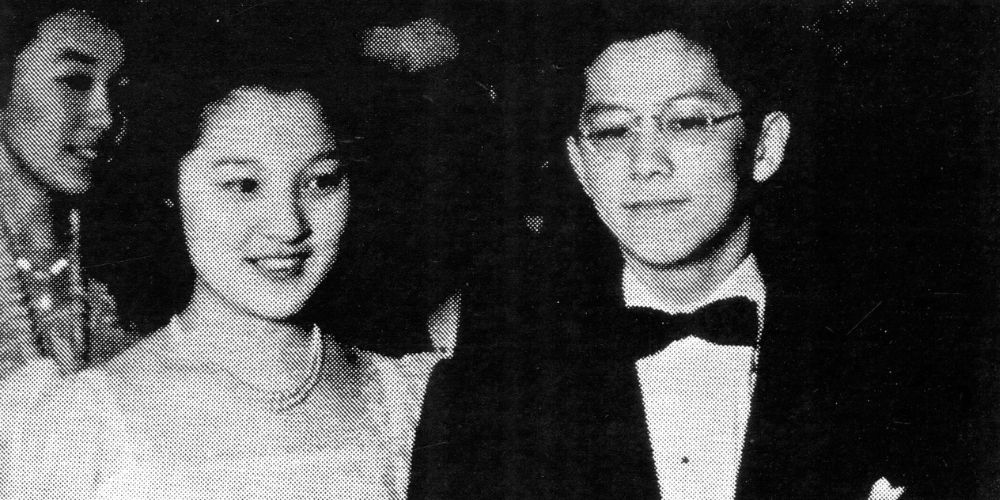

John Nakamura and a friend at the J-Hop Dance at U-M, in February of 1942, from the book “A remembrance.”

A spirit of democracy and tolerance infused the place, and Nakamura was at the heart of it. Everyone saw him as gracious, cheerful, and calm. He was the first to welcome a new resident. As house steward, he managed the kitchen and made up the menus; he enjoyed cooking for 40 men and saw it as an opportunity rather than a chore. An English major, Nakamura invited the acclaimed poet W.H. Auden, a visiting faculty member, to come for Sunday dinner. He loved playing Artie Shaw records and never hesitated to drop the needle on his favorite, “Back Bay Shuffle.”

Nakamura was an early riser and always roused his roommate, Orval G. Johnson, in time for breakfast. “John did not yell nor did he shake me, but instead provided the most civil of wake-up calls: He recited poetry to me,” Johnson said. A favorite poem was A.E. Housman’s “Reveille” with Nakamura quietly urging, “Up, lad, up, ’tis late for lying.”

Everything changed with Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 and America’s entry into World War II.

Housemates dropped out to enlist.

Whenever a newspaper published a horrible political cartoon misrepresenting Japanese people, Nakamura showed it to everyone—he wanted them to know how upsetting it was to him and his family. In Flint, Nakamura’s father, a native of Japan, was laid off from his design job at Chevrolet after the automaker took on war work and considered him a security threat.

U-M offered an accelerated wartime study program, and Nakamura graduated in the summer of 1942. He was 21 years old and wanted to be a journalist. The U.S. Army had other plans.

“The Hardest Work I’ve Ever Done”

The Army drafted Nakamura that September and taught him to handle a rifle. Two months later, officers realized they were training a Japanese American soldier and discharged Nakamura, classifying him as an “enemy alien.” American-born children of Japanese immigrants had been banned from the military earlier that year.

John Nakamura (far left, front row) and soldiers in basic training in 1944, from the book “A remembrance.”

Back in Ann Arbor, Nakamura set out to prove his patriotism. He tried to enroll in an Army Japanese Language School on campus but did not speak Japanese. The university denied his enrollment in a military mapmaking course. He traveled to Washington to ask his elected leaders to get him back into the military. Nothing worked, until the Army announced in February 1943 that it would accept Japanese American soldiers.

Nakamura wasted no time enlisting. The Army assigned him to a segregated, all-Japanese unit, the 442nd Combat Regiment Team, and by spring 1944 he was fighting German soldiers in Italy and earning the Combat Infantryman’s Badge. “The badge represents the hardest work I’ve ever done,” he wrote to his family, “but with more of it, let us hope we will all rest easier by the end of the year.”

Waiting for him at home were his parents, William and Elsie; older brother Joseph, who had graduated from Michigan in 1940; siblings Frank, Mary, and Richard, all at U-M; and the youngest, William, who was in junior high.

He shared the beauty of what he saw in northern Italy. He swam in the Ligurian Sea, marveling at the buoyancy of saltwater. He picked fresh fruit to slake his thirst. “We enjoy fresh figs right off the tree—delicious—pears, peaches, plums, all sorts and grades of wine.”

During a break in the fighting, he and a buddy visited the ancient town of Volterra and its many alabaster shops, admiring the work of stonemasons, who made lamp bases, ashtrays, bookends, animal figurines. He befriended one artisan, bringing him chocolate, cigarettes, canned milk, and other items no longer found in local shops. In turn, the craftsman invited Nakamura to his home to enjoy home-cooked meals and moments of family life with his wife and daughters in the Tuscan hills.

“We had some very good times. Sang together, explained our languages to each other, customs. Some American songs have Italian words and we would sing the English words while they sang Italian,” Nakamura wrote. “Mama Rosa and Papa used to say, ‘Your parents would be very glad if they could see you here.’”

He shipped home a tiny elephant figurine carved by his Italian friend and asked his parents to keep it for his return. The artisan’s wife cried when Nakamura said it was time for him to move on.

A Gentleman, A Romantic, A Philosopher

There was more combat, this time in France, and it was particularly vicious. Nakamura and his company moved from village to village, house to house, killing German soldiers and suffering high casualties themselves. By December 1944, they were exhausted.

John Nakamura (Left) and Lefty (Right) standing with two French women singers and other soldiers.

On Christmas Eve, Nakamura and a buddy, Staff Sergeant Hideo “Lefty” Kuniyoshi, found themselves in an unfamiliar town along the border of Italy and France. The two soldiers had known each other since boot camp. Kuniyoshi called his friend “the intellectual in our squad,” always pushing for discussions about current affairs. With an overnight pass and Christmas just hours away, Nakamura wanted to have dinner somewhere, and wanted female companionship.

Kuniyoshi cautioned that any women on the streets were prostitutes.

“That’s okay,” Nakamura told his friend. “I’ll explain to them that we don’t have any intention of soliciting and that we just want to celebrate Christmas Eve dinner with two young ladies.” He successfully invited two women to join them for a quiet meal at a restaurant, with Nakamura speaking what little French he remembered from high school classes.

“We thoroughly enjoyed their company, and I guess they were happy that we treated them with respect and courtesy,” Kuniyoshi recalled. “After dinner we bid them goodnight and wished them a Merry Christmas.”

He added: “John was a gentleman, an incurable romantic, and a philosopher.”

A Share of the Fighting

John Nakamura was also fatigued. “Home seems neither near or far away,” he wrote in early 1945. “It’s all something like a dream in which time is lost before it is even noticed to be passing.” He realized he had missed his own birthday.

“Infantry is hard; it doesn’t make one any younger. Twenty-four years and not yet settled,” he told his parents. “One must live some sort of life and I could never be at ease if I hadn’t gone to take my share of this fighting.”

He said he wanted to stay in France after the war—“study French and literature and other things that interest me”—despite no job prospects. “That doesn’t seem important as long as I can find a truly satisfactory life,” he said.

In April, Nakamura and the 442nd returned to Italy for the Allies’ final push against Germany. The terrain was more of an enemy than the Nazis. Soldiers moved at night, scaling mountain ridges as a human chain, each grasping the rucksack of the man ahead of him; some men crawled on their hands and knees to avoid falling. On the eve of the campaign, Nakamura confided to a sergeant that he expected to die the next day. The sergeant offered to take him off the front line, but Nakamura refused.

The following day, in heavy fighting, a barrage of German mortars and howitzers killed Pfc. John Michio Nakamura. A month later, the war in Europe was over.

Tribute to a Fallen Soldier

In 1948, the U-M campus was settling into a post-war rhythm. University leaders announced the Phoenix Project, a research memorial to U-M’s war dead that would develop peaceful uses of atomic power after the destruction unleashed on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Enrollment was higher than ever, with veterans using GI Bill benefits to crowd into classrooms.

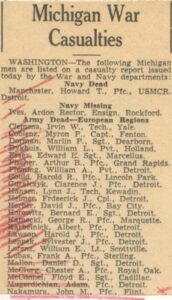

List of Michigan war casualties from John Nakamura’s Alumni File.

On South State Street, the Inter-Cooperative Council prepared to open the newest cooperative house in 16 years of student-owned housing at U-M. Plans for the former boarding house called for 20 rooms for 70 young men committed to the ideals of democracy and interracial living. It would be called Nakamura House, to honor a passionate supporter of co-op life. William Nakamura, the youngest brother of John, later became a resident and the last of six Nakamura siblings to attend U-M.

Three months after Nakamura House opened, the American government moved the body of John Nakamura from Italy to the United States. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery at the request of his parents. The headstone he had tried to imagine in high school was cut from white Vermont granite.

Decades later, friends and family paid tribute to the fallen soldier in a privately published book, A remembrance, John M. Nakamura, January 16, 1921–April 5, 1945, held at the Bentley. Orval Johnson remembered his U-M roommate “as one who had a clear picture of the kind of world he strove for; it would be orderly, caring, healthful, challenging, and benign. In his genteel way he would do his best to create such a world.”

Johnson mentioned the final stanza of the poem that Nakamura often recited:

Clay lies still, but blood’s a rover;

Breath’s a ware that will not keep.

Up, lad: when the journey’s over

There’ll be time enough to sleep.

Bentley sources used in this story include the privately published book A remembrance, John M. Nakamura, January 16, 1921–April 5, 1945, and the Inter-Cooperative Council records.