Magazine

Vaulting Fences, Chopping Wood, and Shocking Delicate Nerves

One of U-M’s first female students defied gender norms and wrote a book about her experiences on campus.

By Madeleine Bradford

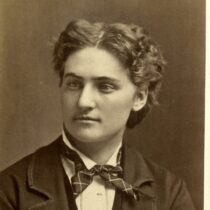

In one photo from the Student Portraits collection, Olive San Louie Anderson wears a suit, waistcoat, and bowtie. In another, she wears a frilled dress, trimmed with lace.

Olive, nicknamed Jo, was among the earliest women to attend the University of Michigan in 1871. Archived images of her gender expression help tell her story, as does her book, An American Girl and Her Four Years in a Boys’ College.

Writing under the pseudonym “Sola,” a rearrangement of her initials, Olive explores the life of “Wilhelmine Elliott,” also known as “Will,” in a thinly veiled description of Olive’s U-M experience.

In this book, while identifying as a woman, Will nevertheless navigates gender fluidly, defying the expectations of the time by cutting her hair short, wearing a hunting suit, and announcing “I’ll never be happy in skirts.” Will faces judgment and social backlash, but clearly feels most comfortable in clothes that don’t fit the gender binary of the time.

Annotations in a Bentley copy of this book, printed from microfilm, show that Will is a stand-in for Olive. Considering her archived photographs, it seems possible that Olive herself enjoyed aspects of men’s fashion from that era, much as Will did.

Olive writes about Will finding women’s dresses cumbersome and hairstyles heavy enough to provoke “headaches.” In one scene, Will burns a corset while giving her friends a speech about dress reform. At the same time, Will is an advocate for women’s rights. She represents herself as masculine one moment, and feminine the next, often combining the two (described as both “boyish” and full of “girlishness,” in the same sentence). She vaults over fences, chops her own wood, and generally challenges what people expect.

“Aren’t you afraid of shocking his delicate nerves?” one of her friends asks, when Will announces she’ll go hunting with a young man she likes.

“Precisely what I want to do, for it must come sooner or later,” she responds.

In 1875, Olive was the only woman in her class invited to give a commencement speech. Will also gives a speech in her book, making a case for women to be allowed into fields “monopolized by men.” This speech may have stemmed from Olive’s own frustrations in her desire to pursue the medical profession. In An American Girl, Will constantly faces people who tell her that women shouldn’t be doctors. Olive would likely have heard the same kind of gendered discouragement.

Olive herself never became a doctor; she worked for a time as a teacher, and a writer, before drowning in a swimming accident in 1886. Nevertheless, her book brings researchers a firsthand perspective of early women studying at universities, the complicated, frustrating world of gender expectations that they navigated, and historical self-expression outside of the gender binary. Several copies of Olive’s book are stored at the Bentley Historical Library, and online in the HathiTrust Digital Library.

[Lead image: Olive San Louis Anderson wearing men’s clothes circa 1875]