Magazine

We Demand Education

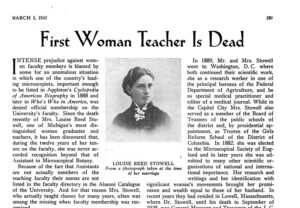

The first woman hired to teach at U-M was Louisa Reed-Stowell, a brilliant botanist who fought tirelessly for women’s equality, especially in education. Despite her prestigious contributions in the field, in the classroom, and beyond, U-M would discriminate against her time and time again on promotions, salary, and recognition.

Nevertheless, she persisted.

By Madeleine Bradford

Brilliantly colored flags were draped across the balconies of Albaugh’s Opera House as women streamed into the building. It was March 26, 1888. Outside, freezing rain thundered against the roof.

Inside was just as loud. Newspapers described the crinkling of long coats and squeaking of galoshes, mingling with a hum of excited voices. People quickly filled the seats, settling into the largest theater D.C. had to offer at the time.

They needed the space. The Baltimore Sun reported that the first International Council of Women (ICW) had an audience of at least 800.

Speakers would spend the next several days calling for equality, for women’s education, for involvement in politics, for the right to vote. Along would come Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Frederick Douglass—and, on this first day of speeches, Louisa Reed-Stowell of Ann Arbor.

Women’s education was the topic of the day. Reed-Stowell asked the audience to imagine the year 1854, when American women’s access to education consisted of hearing men recite their lessons on the school steps.

“We demand education that can give efficiency to the intellect, light to the feelings, and dignity to the whole character,” she said, quoting one of those women. Some men claimed women only needed education on “culinary matters,” Reed-Stowell said. She brandished another testimonial, reading aloud:

“We claim the opportunity of pursuing the same course of study provided for males, and that this shall be limited only by inclination or capacity.”

Reed-Stowell spoke at the 1888 Council as a representative for the Western Association of Collegiate Alumnae, but she may have been more well-known for being the very first woman ever hired to teach at the University of Michigan.

Reed-Stowell would never stop encouraging women to learn and supporting the right of women to an equal education. However, she struggled against discrimination; she knew very well that women had a harder time getting promoted, and that their job prospects were not equal. After all, she worked for the University of Michigan as a teacher and expert in microscopic botany for 12 years, starting in 1877.

Despite her achievements, she was never promoted beyond assistant.

Ferns and Crayfish Antennae

Fascinated by the natural world, Louisa Maria Reed entered U-M’s Scientific Course in 1872, just two years after women were first admitted. She faced mixed reactions from a sea of men in bristling beards and sideburns. “Sympathy, admiration, [and] co-operation” came side by side with “criticism, rudeness, opposition,” according to student Harriet Holman, who wrote about women’s experiences at U-M in the 1870s, in her response to an Alumnae Survey in 1924.

Undaunted, Reed hurled herself into learning. U-M’s doors were open to her now, and she spent time in classrooms, the library (well, the women’s side of the library), and among peers—even getting elected as an editor of the sophomore newsletter, The Oracle.

But it was the microscopical laboratory that she fell in love with.

Unidentified woman in U-M’s Microscope laboratory (possibly Reed-Stowell), undated.

Sunlight streamed through the laboratory windows, crucial for microscopic work at a time when Edison had yet to sell his first incandescent light.

Here, Louisa Reed tilted the circular mirror under her microscope back and forth, just so, reflecting a beam of light into the slide she hoped to examine. She peered through the lens at the cross-section of a fern’s stem, lit up like a stained-glass window.

She began to draw.

She labeled drawings of everything from lilies to crayfish antennae, in swift, spidering cursive. Her work was exquisitely detailed—and people noticed. Microscopic photography was still a rarity, making scientific drawing a critical skill.

Published in places like The Therapeutic Gazette of Detroit and the Scientific American, her “pen drawings” would go on to be described by the St. Louis Medical and Surgical Journal as “equal to photomicrographs.”

Studying during the school year wasn’t enough; Louisa Reed eagerly volunteered at the University Museum during breaks. She was soon called “indispensable.” Using her keen eye and love of plants, she helped develop and catalogue herbarium collections for 16 years, starting the year after she enrolled.

Her bachelor of science degree was granted in 1876. Her master’s degree in science in 1877 quickly followed (as did her marriage to Charles Stowell, another microscope enthusiast, in 1878). Her passion for museum work landed her a job upon graduation: she was kept on as a museum assistant and paid $30 a month. The quietly momentous decision was made, later that same year, to offer her a position as assistant in the microscopical laboratory.

Hired for the laboratory position in October 1877, she would hold this title in the Botany Department until 1889. At first, according to the University of Michigan: An Encyclopedic Survey of U-M, she acted as the title suggests: an assistant to Professor Volney M. Spalding, as he taught classes in microscopy.

Then, she began to teach.

Beyond Doubt

The University soon relied on Reed-Stowell to provide courses in “structural botany, histology, pharmaceutical botany, and microscopy,” leading, by herself, half of the botanical courses U-M offered at the time. She was even asked to sign diplomas as a member of the faculties.

When Byron M. Cutcheon, an Ypsilanti Civil War veteran and former U-M regent, wrote an opinion piece in the student publication Castalian in 1896, he declared that women should be hired as University teachers. He cited his memory of Reed-Stowell’s exemplary work as an instructor.

That was how she was remembered: as an instructor. Not an assistant.

“The day is gone by,” Mr. Cutcheon wrote, “in my judgment, when a woman can be barred from any field of work … simply because she is a woman.”

Title page of Reed-Stowell’s Microscopic Drawings book, now archived at the Bentley Historical Library.

Yet even as Reed-Stowell’s husband, Charles Stowell, was promoted steadily over the years, rising from instructor, to lecturer, to assistant professor, to professor of histology and microscopy; even as the two co-founded and co-edited the scientific journal The Microscope; even as they co-wrote a book on Microscopical Diagnosis (which Reed-Stowell additionally illustrated); even as she taught classes, signed diplomas, and was elected as the first American woman ever to join the Royal Microscopical Society of London—her title remained “assistant.”

Her husband was furious on her behalf. Charles Stowell later wrote a frosty letter to the University, noting his wife’s achievements, and the fact that her work had been omitted from an edition of the General Catalogue of Officers and Students, a publication compiling the names of previous students and staff.

“She received many letters from her old pupils protesting against such action by the catalogue committee, but of course that availed nothing,” he wrote. “If the University accepted her work as an instructor, why should it not now give her credit for the same?”

Reed-Stowell “was very successful in instructing,” Professor Harley H. Bartlett wrote, in a typewritten draft of Botany at the U of M through the first Century. Yet “the vexing problem of Mrs. Stowell’s title” remained.

“The Regents gave her an increase of pay for the year 1879–80, but, not knowing just what to call her position, compromised by calling it nothing at all,” Bartlett wrote.

Her salary, incidentally, became precisely the same amount her husband made when promoted to instructor—a title she was never awarded. A promotion for Reed-Stowell to assistant professor was even recommended in 1882, when a committee proposed the creation of a new microscope lab.

The promotion was never given.

Still, the lack of recognition for her work was not enough to discourage her.

At a time when “women had no place on campus where they could rest or meet in groups,” according to the Michigan Alumnus magazine, Reed-Stowell “secured permission for the use of a room” for early coeds, creating a kind of parlor where women could gather, study, and socialize. She brought furniture from her own house to fill it. Her support for students was constant; Fanny K. Read, a graduate of the class of 1890, remembered her as the “only woman advisor” during her years at the U-M.

Beyond the classroom, she advocated for women’s postgraduate education to the Western Association of Collegiate Alumnae (WACA) in 1875. She became WACA’s president in 1887 and would give her speech at the International Council of Women just one year later.

She clearly meant it when she said that an “unending effort” to prove the importance of higher education for women was the “duty of our time.” She believed strongly in supporting other women to learn, and to keep learning. She knew very well that a love of learning was not restricted by gender.

Speaking Up

“Her title did not do justice to her responsibilities and attainments,” the U-M Encyclopedic Survey would later acknowledge, adding: “She certainly deserves recognition as the first woman instructor of the University.”

Yet, in the face of what the Michigan Alumnus called “intense prejudice against women teachers,” she decided to speak at the 1888 International Council of Women, and demand that equal access to education be considered seriously.

Inclusive Education

A debilitating, unnamed illness struck Reed-Stowell in 1889. Unable to keep teaching, she left U-M to work in the U.S. Department of Agriculture, again as an assistant microscopist. Later, she continued her work in the field of education, as one of the first women trustees of the school board for the District of Columbia.

Over the course of her life, she “contributed over 100 scientific papers to leading magazines and periodicals,” according to the 1914 Women’s Who’s Who of America.

The organizations she worked with kept growing, especially the Western Association of Collegiate Alumnae, which she represented at the ICW. The organization would eventually become the American Association of University Women (AAUW). They’re still supporting women today, and are, according to their website, “one of the largest funders of women’s graduate education” since 1888.

The Michigan Alumnus noted Reed-Stowell’s passing in March, 1932.

The ICW has expanded, too. It continues to advocate for women’s rights, consulting with the United Nations on topics including women’s access to nutrition, clean water, literacy, and leadership. From the nine initial countries, it has grown to a membership of 70 countries around the world.

Reed-Stowell thought of Ann Arbor as her hometown. When she died, she was buried in Forest Hill Cemetery. She left a collection of microscopes to the University of Michigan, and her written words, many housed at the Bentley, encourage others to continue her work.

“The genius of the American college is not in sympathy with any ruling that excludes from the halls of learning any person, or class of persons, who desire their advantages,” Reed-Stowell said during her 1888 speech. She called it a “prophecy” that people would one day see what she considered to be a simple truth: Education should be inclusive.

To see more of Louisa Reed-Stowell’s work, the Bentley holds a volume of her microscopic illustrations, her co-written book Microscopical Diagnosis, her co-edited journal, The Microscope, and her “Pamphlets and Reprints.” Her diploma from the University of Michigan was also preserved and can be shown in the Bentley’s reading room. The Bentley’s digitized Alumnae Surveys are an excellent resource to learn more about the experiences of early women at the University.