Magazine

What Time Is It Now?

Trains crashing. People dying. Businesses struggling. The perils of keeping incorrect time in Detroit were significant, and the city desperately needed a solution. A visionary academic, a knowledge-loving businessman, and new technology to plot the stars would converge on a small hill at U-M, changing Detroit—and the campus—forever.

By Andrew Rutledge

For thousands of years, humanity had little need for or interest in knowing what time it was.

It was enough to glance up for a sense of how long until dawn or dusk. It wasn’t until the 1800s that this needed to change. As more and more Americans were drawn to the factories of industrializing cities, their days were increasingly governed not by the sun, but by the chime of the clock. This created a new need for widespread and accurate timekeeping.

Perhaps nowhere was this more true than in Detroit. The growing hub of the industrializing Midwest was bedeviled by inaccurate and haphazard timekeeping. The railroads that ran through the city used different times from each other, causing unending chaos for travelers and goods. Michiganders wandering the city’s streets were sonically assaulted by the discordant chiming of clocks, each running on its own time.

Something needed to be done.

Enter the Detroit Observatory. Papers at the Bentley Historical Library reveal how Michiganders turned to the astronomers of the University of Michigan for help finding and regulating accurate time. The University’s first President, Henry Philip Tappan, envisioned the observatory as placing the school at the forefront of scientific research—and it did. It also helped usher in an era of prosperity and temporal order throughout the state—and beyond.

The Dangers of Railroad Time

From the first steam locomotive’s journey through Baltimore in 1829, railways exploded across the United States. By 1850, more than 5,000 miles of track had been built; by 1860, more than 80 percent of farms in the Midwest were within five miles of a railroad track.

The spread of railroads and their rapid travel speed tied American society together in a revolutionary way and made time differences between cities more stark. Before this, when it took days to travel between Detroit and Kalamazoo, the 10 minutes’ difference in local time (determined by sundial) made no difference. But when a trip by train took only a few hours, the time difference was much more noticeable.

Griswold and State Streets in Detroit circa 1880, with a view of Capitol Union High School.

To account for this, and to simplify the process of calculating a train’s location, railroads noted the local time at one station, then set the clocks at each station, as well as the conductors’ watches, to that same time. Known as “railroad time,” this system meant that no matter where a train was physically, its time was standardized along the whole line. This meant timetables would be accurate at every station. Depending on a station’s location, these timetables could be quite different from local time. For example, the Michigan Central Railroad used Detroit time since that is where it was headquartered, but this was 42 minutes ahead of the local time at its station in Chicago.

This issue of time difference was made even worse when a town had multiple railroads. In 1864, the four railroads that passed through Saginaw ran on three different time schedules: Chicago time, Detroit time, and Hamilton, New York, time. All of these differed dramatically from local time.

As “railroad time” became more confusing, and as railroads expanded across the nation, more and more accidents occurred. Between January and August 1853 alone, at least 66 railroad collisions left more than 190 people dead and nearly 400 injured. Many of these accidents were caused by inaccurate or faulty clocks, or by differences in the time used by different railroads on the same track. A public outcry arose over what The New York Times described as the “wholesale slaughter by railroad trains,” while businessmen fretted not only over the loss of life, but the destruction of the goods trains transported.

Railroad industry leaders were not the only ones interested in a more uniform time; the public wanted it too. One Detroit newspaper laid out the frustrations of time in the city:

When persons speak of “Detroit time,” they speak of a very curious and indefinite thing . . . It is here and there and everywhere, and it is rather doubtful it is anywhere. Every man . . . carries the true time according to himself. The bells in the various towers strike at various intervals, as it may happen, often varying from ten to thirty minutes of each other. Amid all this jargon the anxious inquirer after the true time is liable to become hopelessly confused.

One of those frustrated by inaccuracies in timekeeping on both a personal and professional level was Henry Nelson Walker. A lawyer by training, Walker had migrated to Michigan from New York in the 1830s. He had served as Michigan’s Attorney General before becoming involved with the rapidly expanding banking and railroad industries. Eventually, he became Vice President of the Detroit Savings Bank and President of the Detroit, Grand Haven & Milwaukee Railroad Company. He was also the President of the Detroit Young Men’s Society, perhaps the most powerful cultural force in the state, which hosted public lectures and debates on scientific, political, and historical topics. Walker was keenly interested in the problem of time.

A Vision of the Stars

Walker’s solution presented itself in the form of the University of Michigan’s first president, Henry Philip Tappan.

Long a critic of the state of America’s colleges, Tappan complained that “in our country we have no universities . . . They have neither libraries and material of learning, generally, nor the large and free organization which go to make up universities.”

When Tappan arrived in Ann Arbor in 1852, he gave a speech outlining his vision for a new type of university. Drawing on the German model, he sought to transform the University of Michigan into an institution where knowledge was not just taught, but created. He argued that learning must be valuable to society as a whole, for “literature, science, arts, educational apparatus, and labor all increase the commodities of trade, and add to the national wealth.”

Tappan proposed creating a scientific curriculum that incorporated mathematics, civil engineering, chemistry, the industrial arts, and “astronomy with the use of an observatory.”

One of those listening to Tappan that day in 1852 was Henry N. Walker. Identifying with Tappan’s vision, Walker approached the President after his speech and asked how he could support his efforts. Tappan replied that he could help by funding the construction of an observatory.

The observatory wouldn’t just put U-M on the map as a great American university in keeping with Tappan’s vision, it would also solve the problem of time.

This was because, due to the way astronomers recorded the location of stars, they had long been obsessed with time. Astronomers used a system similar to longitude and latitude, but with one key difference: they measured their longitude in hours, minutes, and seconds instead of degrees. As a result, absolute accuracy in timekeeping was required to chart an object’s location in the sky.

Walker swiftly arranged a meeting for Tappan with other prominent Detroiters who agreed to donate funds for an observatory. Tappan had only “contemplated to secure a large telescope and erect a suitable building,” but Walker suggested adding a second telescope to the project: a meridian circle.

Meridian circles were the main means by which astronomers calculated astronomical time. They are aligned on a north-south line and cannot move left or right, only vertically. When a star appears in the field of view, the meridian circle makes two measurements: the time at which the star crosses the meridian as it travels from east to west, and the angle of the star above the horizon. From these, local time can be calculated with extreme precision.

Walker personally donated $4,000 ($130,000 in today’s dollars) for the meridian circle, while other donors provided funds for the rest of the observatory.

The Detroit Observatory, circa 1875.

With these donations, Tappan traveled to Germany, where he commissioned the creation of one of the finest meridian circles in the world. With a magnifying power of up to 288 times the human eye, it could see the stars with great precision. Illuminated “spider threads” set into the lens allowed for the precise timing of the passing of stars across its face. To calculate celestial latitude, the two circles on either side of the telescope were covered with angle markings so small and precise they had to be read with a microscope.

In gratitude to its sponsor, Tappan dubbed it the Walker Meridian Circle. And in gratitude to the rest of the donors, its home was named the Detroit Observatory.

Time for Progress

The Detroit Observatory was completed in 1857, but it was not until 1863 that it began providing relief to time-addled Michiganders. In September of that year, the observatory’s Director, James Craig Watson, grandly announced in Detroit’s newspapers that he had reached an agreement with the jeweler Martin Smith of M.S. Smith & Co. to send “by telegraph at five minutes past five o’clock P.M. precisely, the correct time for your city, derived from transits of stars observed at this Observatory.”

Every morning, an employee of Smith’s would haul a four-foot diameter red canvas ball up a pole on the business’s roof, which was connected by telegraph to the Observatory. When the highly precise clocks at the observatory showed noon in Detroit, Watson would strike a telegraph key, causing the ball to fall. The sight of a large red ball, dropping from 150-feet above the ground, must have been visible to most of the city.

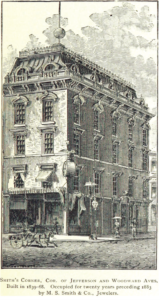

Etching of M.S. Smith & Co. showing the ball that marked “Detroit time” each day at noon.

Not to be outdone, the jewelers Roehm & Wright swiftly erected their own time ball also controlled by the Detroit Observatory at their store next to Detroit’s opera house. Soon other public clocks, such as the Central United Methodist Church clock, also began using the new “city time” supplied from the observatory. Time in Detroit became standardized.

In the wake of this new service, the Michigan Central Railroad decided to adopt the observatory’s “Detroit time” across its entire operation, which stretched outward from Detroit to Chicago, Toledo, Mackinaw City, and across Ontario. Time was sent along more than 1,000 miles of track from Detroit.

As time traveled with the trains, many towns along its tracks decided to end confusion by adopting “railroad time” as their local time. Thus, a uniformity in time began to emerge across the Midwest, paving the way for the eventual creation of modern time zones.

Cost, Benefit, and Legacy

Henry Tappan did not get to see his observatory standardizing time. In June 1863, he was dismissed by the Board of Regents following a decade of clashes and controversy over a variety of issues, including his “Eastern Airs,” his support for the “foreign” German system, a controversy over establishing a college of homeopathic medicine, and the costs of the observatory.

Nevertheless, he had transformed the University of Michigan into a place where knowledge was created, not just learned, and where public service was a core element of its mission.

The Detroit Observatory continued transmitting time signals for nearly 40 years, only halting with the expanded use of standardized time zones in the early 20th century.

The observatory still stands on the University campus today, along with its original instruments. A new 6,000-square-foot addition to the observatory, completed in 2021, has once again made its centuries of science relevant, illustrating key scientific concepts that are still applicable today.

For more on this boldly reimagined new space, please visit: detroitobservatory.umich.edu