Magazine

Where Manhood is Drugged and Destroyed

by Robert Havey

Temperance icon Carrie A. Nation stormed into Ann Arbor in a black horse-drawn carriage on May 2, 1902 at the zenith of her fame and infamy. Nation and her trademark hatchet had made headlines with raids on saloons in her native Kansas. The University of Michigan was one of the first stops on her tour of the nation’s top schools. She wanted to warn college-age students about the evils of booze.

Nation knew firsthand how the scourge of alcohol could ruin a life. Her first husband drank himself to death just two years after they were married, leaving Nation to care for their child alone. Shortly afterwards, she felt she had a revelation from God telling her to “take something in your hands, and throw it at these places…and smash them.” She obeyed, blasting into saloons and damaging property in the supposedly dry state of Kansas. Nation and her followers hacked open casks, shattered liquor bottles, and destroyed bar fixtures. She would eventually settle on a hatchet as the best tool for the job.

American adults in the 19th century drank three times as much as today, according to U-M alumnus Daniel Okrent (’69) in his book Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition (Scribner, 2011). Women often were the victims of alcoholism through lost family income, domestic violence, and/or widowhood. Consequently, the temperance movement consisted mostly of women.

Early temperance advocates wanted moderation in America’s drinking habits, but radicals like Nation thought the only solution was complete Prohibition.

Ann Arbor was not immune to the boozy blight. A riot by drunken students in 1856 led to a “gentleman’s agreement” between police and saloon owners to prohibit the sale of all alcohol east of Division Street. It was thought that if the students had to go off campus for their liquor, it might curb the habits of some of the more voracious drinkers.

Nation’s first stop in Ann Arbor was a visit to a Main Street saloon run by the notorious Dr. Rose. The patrons and onlookers were nervous. Was she going to smash all of the alcohol? No, she was only there to challenge Dr. Rose to a debate that night, offering him $50 if he’d merely attend. Dr. Rose declined by way of fleeing out the back entrance.

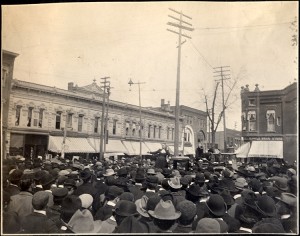

Carrie Nation speaks to the large crowd assembled at the northwest corner of U-M’s campus on May 3, 1902 in this image from the Bentley archives. The student publication The Wolverine poked fun at the visit from the temperance crusader, saying that the various hecklers would “shmoke, shmoke and shmoke in the hereafter” for disrupting Nation’s visit. In her memoir, Nation reflected on her Ann Arbor stop, writing, “I have been to all the principal universities of the United States. At Cambridge, where Harvard is situated, there are no saloons allowed, but in Ann Arbor, the places are thick where manhood is drugged and destroyed.”

Next, Nation accepted an invitation from the Woolley Club for a banquet in her honor. The dinner took place in a hastily decorated kindergarten classroom off campus. Nation said in her memoir, “It gave me new life to look at such men of intellectual and moral force.”

She said her hosts were “giants of moral and physical manhood” unlike the “dull brained sottish students” she had met in the saloon. Nation never caught on that the Woolley Club was not a real University of Michigan organization at all, but a group of prankster students wanting to see if they could pass for hardline prohibitionists for a night.

The next day Nation parked her carriage on North University and State Street to give a speech to the assembled crowd. She shouted over adulation and jeers as she recited Bible verses and urged attendees to vote for the Temper-ance ticket. A man pushed his way up to the wagon in the middle of the speech to ask Nation to smash a bottle of whiskey he had in hand, saying that he was going to quit alcohol right then and there. Nation hurled the bottle on the ground where it burst into shards. The crowd recoiled, not at the broken glass but from the awful smell. The bottle contained hydrogen sulfide, the compound that gives raw eggs their odor. Nation was unaffected by the prank, not letting the sarcastic cheers stop her from finishing her speech. She rode away to rowdy applause.

In 1903, a year after her visit, Ann Arbor passed the Division Street agreement, a law prohibiting alcohol sales on the east side of town. Sixteen years later, Michigan banned all alcohol sales, followed in 1920 by the Eighteenth Amendment making Prohibition the law everywhere in America. (The Division Street divide stayed on the books until 1969, but it was largely ignored after Prohibition was repealed.)

Nation didn’t live to see Prohibition’s rise and fall. She died on June 9, 1911. While her temperance movement ultimately failed, it created a platform for women to advocate for suffrage, the creation of public schools, and equal pay for equal work. Women were becoming more and more a part of the political landscape, and Carrie Nation, hatchet in hand, had paved the way.