News Stories

“America Back to God”

by Mary Jean Babic and Alex Boscolo

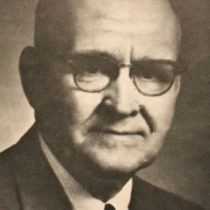

Before televangelists and megachurches, there was John Zoller, who began preaching on the radio in 1924. By the time he died in 1979, his “America Back to God” program reached hundreds of thousands of people in places as distant as South Africa.

Born to a religious family in 1889, John Edward Zoller found his calling in spreading the word of God. In the early years, this meant travelling across the small towns of Michigan to preach the good news to any congregation that would have him.

Then there arose in the land a glorious invention, seemingly heaven-sent for a foot-weary evangelist intent on saving as many souls as possible: radio.

Instantly recognizing the medium’s power, Zoller would go on to become a radio pioneer and build a movement, “America Back to God,” that reached hundreds of thousands of people in places as distant as South Africa. Zoller’s ministry also churned out pamphlets and held prayer meetings, but it was centered on radio broadcasts.

“Radio,” Zoller wrote in the 1950s, “reaches men who could never be induced to enter a church.”

The Zoller collection at Bentley Historical Library includes transcripts of his radio sermons, pamphlets, and his autobiography, The Life Story of Dr. John Zoller. The materials shine a light into the significant role of religious broadcasting in the growth of radio in Detroit and beyond.

A Changing World

The first person ever to make a public broadcast was Canadian inventor Reginald Fessenden in 1906, but radio didn’t really boom until the early 1920s. This was a time of churning social change in the United States. After the horrors of the first world war, attitudes were shifting toward a more libertine outlook. Women bobbed their hair and raised their hemlines, and revelers danced the Charleston while the stock market soared. Urban populations grew; church attendance dropped. Automobiles became more affordable, offering freedom and mobility as never before.

Scientific thought, and especially social Darwinism, was gaining broader acceptance, somewhat to the alarm of religious communities. Threatened by the spread of secularism, a group of prominent Protestants had published “The Fundamentals: A Testimony to the Truth,” a four-volume set of essays defending core Christian beliefs in 1909. These essays laid the groundwork for the modern evangelical movement as its known today. In 1920, Prohibition became the law of the land. Temperance was, at its core, a religious movement aimed at banishing the evil of intoxication. It lasted 13 years.

Even if church pews were emptier, plenty of people were seeking a direct experience of God. Along came radio, at just the right moment, to deliver it.

Zoller Hits the Airwaves

Zoller was ready. In 1923, he was part of a small movement of early adopters. Personal radios were not yet common, but Zoller studied electrical circuitry and quickly became adept in the workings of these early devices. He even offered free public lessons in how to build one at home—more ears for the Lord.

John Zoller and his wife, Ora Zoller, at WMBC in Detroit. Undated photo from the Life Story of John Zoller.

In 1924, Zoller finally tried his first radio broadcast from Flint. It was a stormy Sunday night, and he feared no one would be able to listen. Speaking into what seemed like the void, he begged anyone to let him know if they accepted the Lord because of his broadcast—or if they could even hear him.

The following Thursday, he received a letter from a man in Ann Arbor. “There was something in your voice that compelled me to listen,” the man wrote. “You showed me my need and how God would bless and use me if I would surrender my life to the Lord, so I made this decision, and I am glad I did!”

The Radio Program Grows

Zoller had the good fortune to be situated near southeastern Michigan, which emerged as an early leader in the new radio landscape. WWJ in Detroit was among the first radio stations in the United States, going on air Aug. 20, 1920. Like many early stations, WWJ was established by a newspaper, the Detroit News. This prompted a response from the competing Detroit Free Press, which launched its own station, WJR, in 1922.

Sports, politics, and news accounted for much radio content in the early days. In 1925, Calvin Coolidge was the first president to be inaugurated live on radio. Station owners also added music, drama, vaudeville, and even bedtime stories to attract audiences. In the ecumenical spirit of radio programming in those days, religious shows also found their way onto the dial, and Zoller was among a small but growing contingent of godly men pushing the capabilities of this new medium. Another was Father Charles E. Coughlin, who began broadcasting on WJR in 1926. Known as “the radio priest,” the controversial Coughlin—who was an anti-Semite—attracted an international audience of 30 million at his peak in the 1930s.

In 1928, Zoller was transferred from Albuquerque, New Mexico, to a new church in Flint, and seized opportunity to once again try radio. He went directly to Frank Fallin at WEAA and persuaded Frank to give him a half hour of air time each morning and two and a half hours of air time every Sunday. It was an ambitious proposal, but, he explained, he “believ[ed] in publicity; this is in keeping with God’s Holy Word.”

Thanks in part to his unprecedented use of local advertising and his regular presence on the radio, Zoller’s following began to grow. Speaking in plain, straightforward sentences, he preached a down-home Christianity that sought to combat modernism. Zoller’s tenets were simple: Man is sinful and must repent. The Bible does not contain the word of God; it is the word of God. Any preacher who claimed otherwise was in Satan’s grip. Hell is real. The only way to avoid it is to accept Christ’s sacrifice as your salvation.

Zoller didn’t have a classic radio voice. It wasn’t mellifluous or deep, but he used it to full effect, crescendoing and falling and vibrating to drive home God’s message. His charisma shone through, and even over the radio his passion for bringing lost sheep into the fold was palpable.

By 1929, his program had grown popular enough that the city of Lapeer, Michigan, 21 miles east of Flint, requested a program on their local station too. In 1933, Zoller used his life savings to sign a contract with WMBC, a regional radio station that covered the entire cities of Detroit and Windsor. He also set up a special system that allowed him to preach live.

“I needed a radio station over which I could bring a message of hope and cheer,” Zoller wrote of this purchase, “telling the people that. . . He will meet the needs of all those who will give Him control of their lives.” He possessed a natural understanding of advertising and, despite being a religious man, could relate to the general public’s reticence towards regular church attendance in the modern age. This was the key to his success, which was about to explode.

A Ministry of His Own

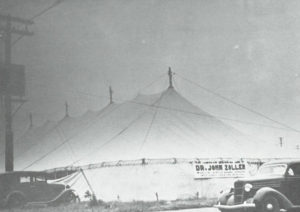

Zoeller’s revival tent in Detroit in the late-1930s. Photo from The Life Story of John Zoller.

In 1938, Dr. Zoller held the first “America Back to God” rally in the massive Detroit Olympia arena that stood on Grand River Avenue and was demolished in 1987. He preached the same tenets of a simple return to honesty and Christianity. This time, though, it was to an audience of over 13,000. Out of this rally grew the “America Back to God” crusade, which spawned not only a radio program of the same name, but a massively successful series of pamphlets, transcripts, and teachings.

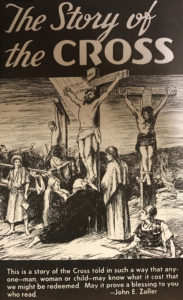

By the 1950s, Zoller was writing monthly pamphlets with his musings on spirituality and prayer. Upwards of 20,000 copies were printed and distributed across the United States and the English-speaking world. A 1945 edition of “Daily Meditations for Busy People” encouraged the importance of small moments of prayer. Inside, letters from Alabama, Florida, South Africa, and Iceland were printed, singing the praises of Dr. Zoller’s sermons and writings.

He also created a series of broadcasts addressed to American GIs serving overseas in World War II, and carried by the Mutual Broadcasting System. The broadcasts were then transcribed into pamphlets. One addressed what Zoller apparently believed to be a great temptation of soldiers: gambling. “I know it’s popular,” he said. “You have the opportunity to gamble; no one will stop you. But dare you do it? Ask yourself the question—‘What effect will gambling have upon my future after the war is over and I return to civilian life?’ In the light of these facts, do you agree with me that it is right and profitable that we prayerfully consider the subject of gambling?”

Another pamphlet bemoaned the lack of Bible reading in public schools, which he linked to juvenile delinquency. “Modern education entirely ignores the Spirit of man,” he wrote. “God is excluded, and the Bible is given no place at all except as literature.” Elsewhere he weighs in on drunkenness, profanity, and adultery—sins all, but forgivable. The worst sin, however, is rejecting Christ, as he makes clear in “The Greatest Sin in All the World”:

One of the radio pamphlets in the Bentley’s Zoller collection.

“There are plenty of wishy-washy fellows in the Service who have no backbone. All they have is a piece of spaghetti. They are afraid to openly confess Christ, the fear of man is keeping them from definitely taking their stand for God.” Perhaps, Zoller muses, they grew up in a prayerful home. “And yet, away from home and away from the influence of praying loved ones you have not manhood enough to step out and openly and publicly confess Jesus Christ. How ashamed you must feel this morning!”

Although he grew popular, Zoller continued to invest most of his money back into the growth of his radio station and the America Back to God crusade. In 1974, he was given a plaque by the National Religious Broadcasters. It reads, “Pioneer Radio Broadcaster – Dr. John Zoller – Friend of Grandmas and Grandpas – Broadcasting the Gospel Over 50 Years.” He passed away five years later, in 1979. He continued to preach until nearly the end.

Today, Zoller is remembered as a pioneer for his groundbreaking innovation and for his decades of dedication. The work of radio evangelists is carried on in modern-day televangelism. Mass media continues to play an important role in the dissemination of religious ideas, and preachers like John Zoller were at the start of it all.