News Stories

Haber’s Labor: Saving the World

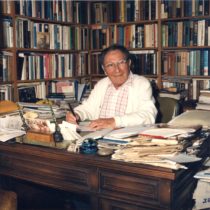

by Terrence J. McDonald, Director, Bentley Historical Library

When Bill Haber arrived in Milwaukee from Romania around 1909, one of his first thoughts was how to raise money to support his widowed mother and four siblings. Hearing that an immigrant could make money peddling newspapers, he and his brother rushed downtown to begin work, even though neither could pronounce “papers,” “peddling,” or “Milwaukee.”

Perhaps it was that early entrepreneurial experience that inspired Haber to major in economics at the University of Wisconsin and remain there for his doctorate in economics in 1927. In 1936, he joined the faculty of the University of Michigan, where he would become William Haber, world-famous economist, author of scores of academic publications, chairman of the Economics Department (1962), and Dean of LSA (1963–1968). And, for a generation of U-M students, he would be the instructor of the labor economics course that they would christen “Labor with Haber.”

But his academic life was only the half of it.

Haber liked to say that his field of economics was “manpower mobilization,” and helping the less fortunate to mobilize into social and economic opportunity was also the focus of his public work. During the 1930s, he held not one, but three positions in the New Deal programs in Michigan. At one point, more than 160,000 Michiganders were working in programs he oversaw. During World War II, he again wore many hats, this time in Washington. And, as he liked to say, he did all of this for one salary.

William Haber (far left) with military personnel and unidentified children in Germany. Undated.

But the heart of his public work life was service to refugees and immigrants, starting with the heroic effort to save German Jews from Nazi extermination. He was head of the National Refugee Service (1939–1941), served as adviser on Jewish Affairs to the American command in Germany (1945–1948), and had a long-term commitment as President of the American Organization for Rehabilitation Through Training Federation (1950–1975).

In these positions, he met the heroes and villains of the 20th century, including those struggling to get Jews out of Germany before World War II — all while America shamefully sat on its hands. Haber helped “displaced persons” in Germany find their futures: Of the 850,000 people in so-called displaced person (DP) camps, 250,000 were Jewish survivors of the Nazi death camps. Later, Haber worked with Jewish immigrants and refugees all over the world to find the economic training and skills to make them a welcome presence in their new societies.

His teaching was so rich because it was so full of concern for the world. “Labor” was not an abstraction for Haber. His magnificent story and personal heroism are well told in his archives at the Bentley, which include the transcripts of a marvelous set of oral history interviews recorded in 1978. In the latter, the interviewers ask him an important question:

Q: Why don’t you ever get disappointed in anything?

A: I’m disappointed in the whole world. To live in a world where there is no reason for poverty, and it’s so widespread; no reason for hunger, and millions are hungry in our own country; no reason for war, and everybody’s at each other’s throats; no reason for hatred, and there’s more hatred than love in the world; and a world of refugees, more refugees now than ever.

But this was not really his list of disappointments, rather his list of motivators. He never stopped working on the remedies.

At a time when Americans are ambivalent about immigration and their duty to the suffering millions outside our borders, it behooves us to reflect on the whole life of this remarkable man.

And his records remind us of the function of archives: They help us to bear witness.