News Stories

Supper Salad is Served!

The Susan Wineberg cookbook collection at the Bentley provides insight into the murky (and sometimes wobbly) depths of Jell-O salad.

by Alex Boscolo

Pictures don’t do it justice. They don’t capture the vivid colors, the suspended objects, the way it moves with the slightest nudge of the table. Is it a piece of art? Is it edible? Is it something out of a bad horror movie?

The infamous Jell-O salad might be all of these things.

The glistening concoctions have names like “Perfection Salad,” “Veal Loaf,” and “Fruit Soup.” The Jell-O salad was an American dietary trend that reached its zenith in the late 1930s and continued to be a key staple of any dinner party or potluck well into the 1970s and ’80s. Carolyn Wyman, author of Jell-O: A Biography, claimed that at one point, gelatin recipes took up more than a third of the salad section in any cookbook. The Susan Wineberg Cookbook Collection at the Bentley Historical Library proves her right.

Wineberg’s collection, which the Bentley acquired in 2010, contains a series of 20th century cookbooks and recipe books from Michigan manufacturers, churches, businesses, and individuals. At least 34 of them have gelatin recipes—and that’s only in the first box. But why so many?

To understand that, we have to go back.

A Shimmering Aspic

People have been eating gelatin since the Middle Ages. Until the late nineteenth century, gelatin was largely consumed by only the most wealthy people since it was a hot, painful process that involved boiling animal bones for hours, according to Sarah Grey, author of the online article, “A Social History of Jell-O Salad.”

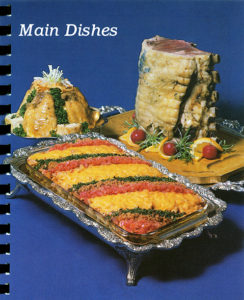

One of the cookbooks in the Susan Wineberg collection containing various Jell-O recipes.

By the mid-1800s, gelatin was commercially available in dried sheets, but they were huge, and took time to soak and reform. In 1893, Knox produced the first gelatin powder. Jell-O brand followed soon after.

Product growth was slow at first. Wyman wrote that one of Jell-O’s early owners sold his stakes because he didn’t believe in its success. Slowly but surely, however, Jell-O began to gain popularity. It was easy to make, affordable, and it was certainly helped by the high social status of homemade gelatin. While homemakers weren’t attempting to convince anyone that they had spent hours slaving over animal bones, they were cashing in on gelatin’s connotation: because it took a long time to make, people considered it fancy.

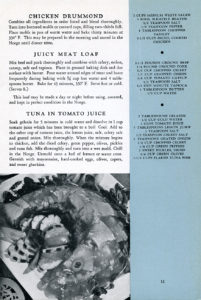

Jell-O proved a godsend to women trying to create healthful and aesthetically pleasing meals. For example, the 1941 Norge Cold cookbook from the Wineberg collection, published by a refrigeration company, suggested making tuna in tomato juice gelatin, molded into a fish shape — giving consumers protein and beauty, all in one. Another cookbook, Around the World Cookery With Electric Housewares, suggested a “shimmering aspic,” that included tomato juice, celery, olives, and strawberry gelatin.

Other organizations with Jell-O recipes or cookbooks within the Wineberg collection include Detroit Kelvinator-Leonard Refrigeration (1940s and ’50s), The White Market in Ann Arbor (1948), Washtenaw Gas Company (1934), and Ann Arbor’s First Congregational Church (1954). No one, it seemed, could escape from the wobbling dessert.

The End of Jell-O Salad

“Tuna in Tomato Juice” Jell-O salad provides protein and visual appeal.

Jell-O salad was not a delicacy meant to last, even with such delights as the “Merry Christmas Salad,” made of lime Jell-O, cream cheese, cottage cheese, pimento, nuts, and crushed pineapple, and cut into the shape of a Christmas tree (Michigan Consolidated Gas Company, 1957).

In “A Social History of Jell-O Salad,” Grey theorizes that the 1980s dieting craze knocked both the dessert and savory salads off the menu in hopes of cutting sugar intake. Plus, she points out, women were starting to enter the workforce in droves. What they were cooking, and how it looked, simply became less important.

Without the social factors that valued its aesthetics and kept it on the dinner table, Jell-O salad (and Jell-O main courses, Jell-O appetizers, and more) became a thing of the past in most circles.

But those who still need their Jell-O fix can scroll down for a few more historical recipes, or they can visit the Susan Wineberg cookbook collection at the Bentley Historical Library.

Supper Salad Recipes the Whole Family Will Love

Cottage Cheese Salad

Ann Arbor’s First Congregational Church: (1954)

1 pkg lemon Jell-O

1 lb cottage cheese

½ envelope Knox Gelatin

1 small green pepper, chopped

1 ½ cup boiling water

Juice of a small onion

2 tbs. lemon juice mayonnaise

2/3 cup diced celery

Dissolve the package of lemon Jell-O and the ½ envelope of Knox Gelatin in the boiling water. When cooled, add all other ingredients and lastly fold in the mayonnaise. Let stand in the refrigerator at least 4 hours to set. Serve on crisp lettuce.

Jellied Swedish Meatloaf

The White Market: The Homemakers’ Meat Recipe Book (c. 1948-1949)

¾ lb liver sausage

1/8 tsp pepper

1 envelope gelatin

½ cup mayonnaise

¼ cup cold water

½ tsp dry mustard

1 ½ cups tomato juice

¾ cup finely chopped celery

2 tsp sugar

¼ cup chopped green pepper

2 tbs. lemon juice

¼ cup chopped stuffed olives

1/8 tsp clove

¼ cup chopped onion

½ tsp salt 1 head lettuce, shredded

Paprika

Rub liver sausage through a sieve. Soften gelatin in cold water. Heat ½ cup tomato juice just below boiling. Dissolve gelatin in tomato juice. Combine gelatin with remaining tomato juice, sugar, lemon juice, clove, salt and pepper. Cool until mixture begins to thicken. Combine liver sausage and remaining ingredients with gelatin-tomato mixture. Turn into a 9-inch ring mold, which has been rinsed with cold water. Chill until firm. Unmold on a chilled platter over a bed of lettuce that has been sprinkled with paprika. 8 to 10 servings.

Party Salad Mold

Carrollton’s Kretschmer Corporation: Good Foods Made Better With Kretschmer Wheat Germ (c. 1940s)

1 envelope unflavored gelatin

3 tbs mayonnaise

¼ cup cold water

2 tbs lemon juice

1 ½ cup boiling water

½ cup Kretschmer Wheat Germ

2 bouillon cubes

1 cup diced, cooked leftover meat

¼ tsp salt

½ cup diced celery

¾ cup cooked vegetables (peas, carrots, beans, pimiento)

Soften gelatin in cold water. Add hot water, bouillon cubes, and salt; stir until dissolved. Cool; add mayonnaise, lemon juice. Chill until partially set. Stir in remaining ingredients. Pour into mold; chill until firm. Makes 6 servings.