News Stories

Ten Burning Buses

By Amy Probst

On a late-August night in 1971, buses were lined up on a quiet lot in Pontiac, Michigan, awaiting drivers and an important school year. As part of an ambitious new phase of court-ordered integration, these buses would be shuttling both Black and white kids to attend school together. That was the plan, at least, until fiery explosions lit the vehicles. Flames were visible for blocks. Firebombs shattered glass and melted rubber, leaving 10 charred hulls by morning.

The Pontiac school bus bombing was one of the largest attacks of the late Civil Rights Movement. And it’s a research focus for Robert Billups, a national fellow at the Jefferson Scholars Foundation in Charlottesville who recently received a Bordin-Gillette Travel Fellowship from the Bentley to uncover more about the Pontiac bombing – and others like it – as part of his Ph.D. work at Emory University.

Billups calls terrorism in response to the Civil Rights Movement anti-civil rights terrorism. He’s researching what he considers a particular strain of violence from the mid-1950s into the ’70s.

Fueled by racism, anti-civil rights terrorism commonly targeted Black people and their homes. “It’s overwhelmingly anti-Black violence,” Billups says, though he adds that some of the violence was explicitly antisemitic or targeted white civil rights allies.

The American South is where most of this violence took place, says Billups, “but anti-civil rights terrorism wasn’t exclusively Southern. And that’s a big reason why I went to the Bentley Library.”

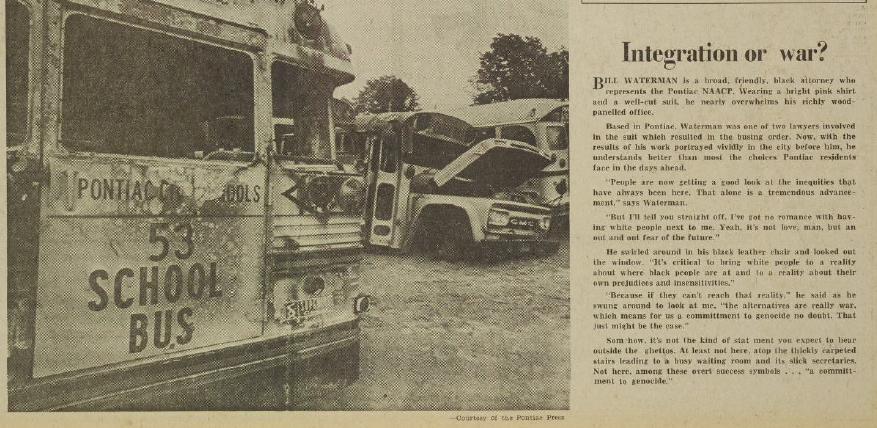

Coverage of the Pontiac bus bombing from The Michigan Daily, September 26, 1971.

Michigan, he says, is significant “both because of the Pontiac [bus] attack and because Detroit was so heavily litigated for its own desegregation plan in the ’70s.”

Weeks after the 1971 school desegregation program commenced, the Pontiac police were investigated by U.S. Marshals for racial discrimination.

After the bombing, six men with ties to the Ku Klux Klan were indicted. Five were convicted in federal court of violating the civil rights of the students in Pontiac and sentenced to federal prison. The prosecution was an anomaly; more commonly, local police or the FBI would develop a broad list of suspects but wouldn’t sufficiently narrow it down to press charges. “That was the norm across the country,” Billups says.

Despite prosecution of the Klansmen, the violence became one of several factors that undercut support for busing. Martha Griffiths, a member of the House of Representatives and strong civil rights supporter since 1954, became increasingly critical of busing, according to her archived papers at the Bentley, which Billups studied. “The Michigan example on the whole suggests that violence tended to undermine support for desegregation via the use of school buses,” he says.

To unearth the incidents of anti-civil rights terrorism, Billups says he uses “all the sources I can, whether it’s oral histories, government records, declassified FBI files, or records from civil rights organizations.” And he makes use of digital maps to show patterns of the violence, where it was concentrated, and studies “the way it changed on the map over time.”

At the Bentley, Billups studied the papers of Griffiths; Phil Hart, a long-serving Michigan senator and civil rights supporter; and William Milliken, who served as Michigan governor from 1969-1983. Milliken’s papers include details about Milliken v. Bradley, a U.S. Supreme Court Case involving desegregation and busing in Detroit.

“The staff really helped me identify the collections that were that were crucial to my work,” Billups says of his research at the Bentley. He now has a full draft of his dissertation completed.

[Lead image: A crowd protesting court-ordered integration in Pontiac, Michigan, from The Michigan Daily, September 26, 1971.]