News Stories

Wartime Football

How U-M continued to play the game, even when America was at war.

by Brian A. Williams

“Football is being played under conditions which would have killed less hardy pastimes.” That is how the 1943 edition of Street and Smith’s Football Yearbook characterized the state of college football in the midst of World War II. Football was a sport short on manpower, even with significantly relaxed eligibility rules. Many colleges were forced to drop intercollegiate football during the war, including Michigan State, which canceled its 1943 season.

Fritz Crisler took pains to assure everyone that Michigan was “conducting its athletic and physical training programs” in a manner “entirely in the interests of our nation’s war effort.” A complication for both fans and the team was war-imposed gas rationing.

The government even asked Michigan to consider moving its games to Detroit for the 1942 season to conserve resources. As Michigan prepared to play its first wartime season in 1942, the application sent to prospective players reflected the new reality. The application asked candidates if they were registered under the Selective Service Act, what their classification was, and most important for the coaching staff, “When do you expect to be called?”

One significant change for the 1942 football season was an overhaul of eligibility rules. Prompted by a loss of manpower through enlistment and the Selective Service draft, the freshman eligibility rule was waived. The rule revision that allowed freshmen to play also enabled soldiers and sailors stationed at military training bases to be eligible regardless of their previous experience. Many of the players on the military base teams had completed their college eligibility and a few had even played professionally.

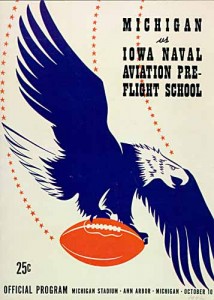

When the Iowa Naval Pre-Flight Seahawks, one of many new military training base teams, came to Ann Arbor on October 10, 1942, to take on the Wolverines, Michigan faced several former Big 10 foes as well as several former Wolverines. The captain of the Seahawks was none other than Forest Evashevski, Michigan’s captain in 1940 and famed lead blocker for Tom Harmon. Evashevski scored the first touchdown for the Seahawks en route to a 26-14 victory. Three other former Wolverines helped the Seahawks beat Michigan.

Unusual Gridiron Talent

Michigan entered the 1943 season as a conference favorite having finished with a 7-3 record in 1942 and a ninth place ranking in the AP poll. However, Crisler’s 1943 squad was one of the most unusual teams he ever fielded.

Ed Frutig was a member of the 1940 All-American “grid squad” and was a 1941 U-M graduate. He’s shown here as a cadet at the Naval Air Station in Corpus Christi, Texas.

The 1943 squad featured just seven letter-winners from the previous team due more to military call-ups than to graduation. Fortunately for Crisler, the loss of players from the 1942 team was more than offset by an embarrassment of riches assigned to Michigan’s campus by the Navy V-12 training program, one of many war-time military training programs housed on the Michigan campus. Unlike the Army, which prohibited its campus trainees from participating in intercollegiate football, the Navy encouraged its trainees to play.

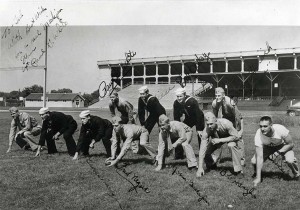

The “lend-lease” football program during the war meant Big 10 champs on U-M’s campus conducting Naval officer training could also join the football team. This was an unexpected embarrassment of riches for the 1943 team. They are: (backfield, left to right) Paul White, Bob Wiese, Bill Daley, Elroy Hirsch; (front, left to right) Art Renner, Merv Pregulman, George Kreager, Fred Negus, John Gallagher, Bob Hanzlik, Rudy Smeja

In July 1943, when Naval V-12 officer training was inaugurated on Michigan’s campus, among those assigned to Ann Arbor were several Big 10 stars including Bill Daley of Minnesota and Elroy “Crazy Legs” Hirsch from Wisconsin, plus ten other players who were on the 1942 Badger roster. According to the Michigan Alumnus these military “lend-lease” players represented “one of the greatest aggregations of gridiron talent ever brought together on one Campus.”

For the season opener against Camp Grant, Michigan’s starting line-up consisted of six marines, four sailors, and one civilian. The lone civilian was a senior engineering student deferred by his local draft board until his graduation. The same blessing that bestowed the array of talent on Michigan also threatened to transfer players away at any time, leaving great uncertainty for the coaches. Captain Paul White was called to active service after just four games. All-Americans Daley and Merv Pregulman were transferred away with several games remaining.

The lend-lease players had to have some conflicting feelings, especially in rivalry games. Daley had helped Minnesota retain the Little Brown Jug all three years he played for the Gophers. In 1943 Daley helped Michigan win the Little Brown Jug back when he scored two touchdowns against his former team and brought an end to Minnesota’s nine-game winning streak against Michigan. On November 13, 11 ex-Badgers all played against their former team in a 27-0 Michigan win. Hirsch, who had bragged earlier about scoring against his former team, was injured and unlikely to play. However, Hirsch made good on his boast of scoring when he inserted himself into the game after Michigan’s final touchdown and kicked the point after touchdown to the surprise of his teammates and coaches.

Michigan’s Service and Sacrifice

Michigan finished 1943 tied with Purdue for the Big 10 title with a record of 8-1 and a third-place ranking by the AP. The lone loss came against a Notre Dame team, also aided by military players, which finished the season ranked as the number one team in the country followed by Iowa Pre-Flight.

In all, more than 13,000 military men and women trained in the various wartime programs housed on Michigan’s campus. Some 32,000 University of Michigan alumni, faculty, and staff served in the military. Five-hundred seventy-nine members of the university community lost their lives in World War II.